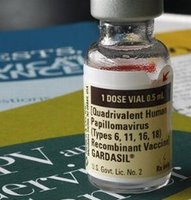

Presentation to FDA intended to raise awarenes of Gardasil cervical cancer vaccine risks

FORT WAYNE, Ind.

A Fort Wayne couple is keeping their fingers crossed that a presentation Friday before Food and Drug Administration officials will open eyes about the risks associated with the Gardasil vaccine.St. Louis, MO DWI Lawyer - Pulledover.com

Multimedia.

Several FDA offices were scheduled to hear testimony on behalf of parents who say their daughters have died or suffered debilitating side effects from the drug designed to prevent cervical cancer.

Dan and Kim Chitwood's daughter Taylor has battled seizures since taking Gardasil shots two and a half years ago.

Kim Chitwood says, “Just very hopeful that this will be presented in a way that, um, nationally and worldwide, people will find out about Gardasil and things that it can cause."

Caleigh Miller of Fort Wayne is also suffering from seizures; a problem her parents are convinced is a result of Gardasil shots.

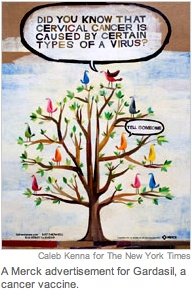

The Centers for Disease Control stand behind the vaccine, as a safe way to prevent cases of cervical cancer that health officials insist will otherwise kill thousands of women.

Labels: Cervical Cancer Prevention, Cervical Cancer Screening, Cervical Cancer Vaccine, Gardasil