If at First You Don't Succeed . . .

If at First You Don't Succeed . . .

. . . Maybe It's Time For a Different Type Of Gastric SurgeryBy Larry Lindner

Special to The Washington Post Washington, D.C.

"For the first time in my life I felt like a normal person," says Josh Thayer, who dropped from 367 pounds to 230 within a year of undergoing gastric bypass surgery in 1998. No longer did he always have to buy the aisle seat at the theater because "you feel guilty hanging over the person sitting next to you." No longer did he have to endure humiliations such as breaking a chair at his brother's wedding.

The best part, says Thayer, a Boston area professor, was not having to "think about food for the first time in my life. It was fantastic. I ate when I was hungry, stopped when I was full. I didn't feel like I was fighting an uphill battle."

Until five years later, when the weight started creeping back on.

When the 6-foot Thayer edged up to 310 earlier this year at age 45, he decided to go for a second operation: adjustable banding, more commonly known as lap-band surgery, which allows for repeated stomach-tightening and thereby offers a new opportunity for reining in appetite. Reactions to his decision vary, he says. While some people close to him worry about his going under the knife again, others have asked, "What the hell did you do wrong?"

Second surgeries to combat obesity are on the rise. The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery doesn't keep statistics on repeat customers, but obesity surgeons are reporting upticks. Dennis Halmi, a member of the Bluepoint Surgical Group in Woodbridge, says that in 2002 "we did a handful" of second operations on obesity patients, "maybe five, six. This year we are doing probably 30." Scott Shikora of Tufts Medical Center in Boston says that until recently he hadn't performed a second obesity operation on anybody but is already up to about a half-dozen patients. Thayer was one of them.

George Fielding, whose obesity surgery practice at the NYU Medical Center in New York has gone from two or three second operations in 2004 to "probably 20 or 25 this year," isn't surprised at the trend. "There was a huge surge in gastric bypass from 1998 to 2001," he says. "Going into the early 2000s, everyone thought the gastric bypass was the best thing since Eric Clapton picked up a guitar. Then they went and hid, then they came in for help."

ad_icon

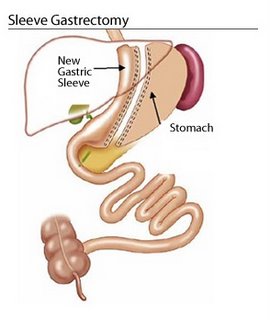

The second time around, many, like Thayer, are opting for the adjustable band, which works differently from the bypass. With a bypass, 95 percent of the stomach is closed off with a stapling device. What could once stretch to the size of a football is reduced to the size of an egg that can't hold more than a tablespoon or two of food. In addition, the small intestine, where food goes when it leaves the stomach, is cut into two pieces. The lower piece, two to three feet down from the upper piece, is connected to the new, tiny stomach pouch. Thus, when food empties from the stomach, it bypasses a few feet of upper intestine, which means that fewer nutrients (including fewer calories) are absorbed by the body.

Obesity surgeons, Fielding included, report a high success rate for the bypass. Bypass patients lose some 60 to 80 percent of their excess weight, and 60 to 80 percent of those patients keep off at least two-thirds of the weight they lose. Such people often experience a near-complete reversal of diabetes, sleep apnea, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, arthritis pain and a host of other health-compromising problems, frequently going from several prescription drugs a day to none.

The thing is, for about 20 to 40 percent of patients, the operation fails over the long term. It's not always clear why. In a number of people, the stomach pouch softens, as does the opening between the stomach and the small intestine. That allows more food through more quickly, and the person's old level of hunger begins to return. As Joseph Moresca, a New York nurse who initially went from 440 pounds to 220 with a bypass, put it, "instead of being able to eat a quarter of a sandwich, I was eating three-quarters of a sandwich." He regained 45 pounds by the time he decided to go for banding.

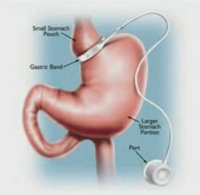

In contrast to the bypass, the band does its work by separating the stomach into two parts: a tiny upper pouch and a larger pouch below the band. The tighter the band, the more slowly food goes from the upper part of the stomach to the lower, reducing hunger dramatically. The operation is far safer than bypass surgery because organs are not being cut and sewn. In addition, there's no nutrient malabsorption as there is with the bypass, because the small intestine is left intact; banding patients do not have to take nutrient supplements for the rest of their lives, the way bypass patients do.

But the biggest difference is that when hunger starts to return, the banding patient can go in to his doctor's office for a tightening. The band is shaped like a little life preserver that can fill and go slack. Saline solution injected into it through a portal just beneath the skin makes it more taut. The tighter the band, the less hungry you are, the less food you can get down comfortably, and the less you eat.

But in that advantage lies the band's disadvantage. If the patient doesn't go in for adjustments, the whole thing won't work. Also, you can eat around, or rather, through, the band. Ice cream shakes and other very soft or liquid foods can go through even a tight band, and every obesity surgeon can point to band patients who have sabotaged their operations by eating foods that slip right through. The ability to control the tightness is presumably part of the reason that patients who opt for banding lose less weight, at least initially, than gastric bypass patients -- an average of 50 to 65 percent of their excess weight in the first three years.

Another difference between the band and the bypass that proves both a plus and a minus is that the band doesn't cause the dumping syndrome. That's an often frightening attack of sweating, nausea, faintness, diarrhea, cramps and rapid pulse that bypass patients sometimes suffer after eating just a bite of a sugary food -- a deterrent to consuming certain calorie-dense items.

Of course, a second obesity surgery comes with increased risk. After a gastric bypass, there's often scarring that causes organs to adhere to one another. "The liver, stomach, spleen and diaphragm -- they all get drawn in together in a big blob of scar," says NYU surgeon Fielding. Thayer says his banding operation, which would typically take about an hour, kept him under general anesthesia for 3 1/2 hours because his surgeon "ran into a lot of adhesions."

Along with the risk comes the uncertainty of how well people will be able to lose -- and keep off -- weight the second time around. Not enough time has elapsed since the advent of second operations to get a long-term assessment.

What obesity surgeons do feel confident saying is that no matter which type of surgery is chosen, and whether it's the first or second time, the patient has to meet the operation halfway. You "still have to follow some semblance of dietary compliance," says Tufts's Shikora. "You also have to be more physically active, take care of your health. And you have to follow up."

In other words, anyone who sees obesity surgery as a solution in itself is chasing weight-loss rainbows.

Thayer, who was down 30 pounds a month after having had his band inserted, gets it. "You still have to diet," he says. "You still have to commit to an exercise plan." No obesity operation is "a magic bullet." But what he misses is that the bypass operation initially let him maintain his weight loss without putting extraordinary focus on his efforts.

Like a lot of other obese people, he says, he "had always been a person who could lose 100 pounds. I did it many, many times. The problem is, I'm not a great maintainer." The bypass, at least at first, let him not only achieve but also maintain the weight loss without thinking much about it. "I didn't have to count calories. I exercised,o but I didn't have to exercise two hours a day in order to stay at that weight."

He wants the new procedure to return his appetite to a more manageable level so that it helps the pounds stay off. "I'm hoping that this band will not allow me to eat a whole pizza anymore," he says. "Last summer I was able to eat a whole pizza again, and I was like, this can't be right."

Labels: gastric bypass surgery alternatives, Lap-Band surgery