Gastric Action: 'Lap-band' surgery for teens gaining acceptance

Charlottesville, VA

Andrew Burrill says that the worst moment occurred last year in his high school cafeteria. Heading for a table, his tray laden with an extra portion of his favorite school lunch, Andrew was intercepted by a teacher who loudly asked, "Are you SURE you should have gotten doubles?" Andrew, who at the time was nearly 5 feet 4 and weighed 260 pounds, burst into tears.

"There were times when I felt I just couldn't go on," recalled Andrew, a sophomore, who lives near Charlottesville, Va. At 15, already a veteran of numerous failed diets, exercise programs and summer "fat" camp, Andrew became convinced that weight-loss surgery, which had transformed the physique of a family friend, was his only hope. He pleaded with his mother for help.

"I had to do this for him, no matter what," recalled his mother, Cheryl Burrill, an IT executive. But when she called hospitals around the country to find a surgeon who would reduce Andrew's stomach from the size of a large grapefruit to the size of an egg, she was told that he was too young and should come back when he turned 18.

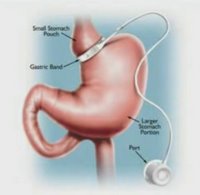

Worried about his increasing girth, high blood pressure and severe sleep apnea, Cheryl Burrill said she didn't think her son could wait three years. Scouring the Internet, she found surgeon Eric Pinnar in Reston, Va., who specializes in "lap-band" surgery. Unlike gastric bypass, which involves stapling the stomach and permanently rerouting the intestines, lap-band surgery is reversible and involves the use of an adjustable band to bisect and shrink the stomach.

Last September, Andrew became Pinnar's youngest patient. Since then the surgeon has operated on four other youths under 18; more are planned.

These youths are part of a growing vanguard of extremely obese teenagers who are undergoing bariatric surgery, as the last-ditch weight-loss operations are known. The procedures, designed for those who are 100 pounds or more overweight, have increased dramatically among adults, from 14,000 in 1998 to nearly 178,000 in 2006.

Although a handful of doctors have operated on children and teenagers, some weighing more than 700 pounds, bariatric surgery has been regarded by many doctors as too risky and drastic for patients younger than 18. A 2007 study estimated that 2,744 teens underwent weight-loss surgery between 1996 and 2003, a number that more than tripled between 2000 and 2003. Many pediatricians and pediatric surgeons have been leery of the procedures, which have not been studied in children, require lifetime adherence to a strict dietary regimen, and can cause hazardous nutritional deficiencies and, in rare cases, death.

That opposition appears to be ebbing. Spurred by improvements in technique and studies in adults showing increased longevity and reversal of Type 2 diabetes and other problems, some influential opponents have softened their resistance. At the same time, the National Institutes of Health is financing a study of gastric bypass involving 200 teenagers, while the Food and Drug Administration is sponsoring a trial of the lap band in patients 14 to 17.

Skeptics say they are intrigued by the possibility that early intervention, before years of disordered eating and metabolic damage have taken their toll, might benefit some severely obese teenagers for whom other treatments have failed. Those hopes were buoyed by a small study published last month in the journal Pediatrics, which reported a resolution of Type 2 diabetes among 10 of 11 teenagers who underwent gastric bypass.

Two other factors are fueling the re-evaluation of weight-loss surgery: the relentless increase in childhood obesity and the dismal results of behavioral treatment, consisting of some combination of diet, talk therapy and exercise. Behavioral treatment has a long-term failure rate estimated at roughly 95 percent.

"We know that the vast majority of morbidly obese adolescents become morbidly obese adults and that medical and behavioral therapy doesn't work for them," said Evan Nadler, the director of New York University's minimally invasive pediatric-surgery program who is involved in the FDA lap-band study. "These kids are sick. This is truly a disease, a problem we can treat with the best means we know how. (Surgery) is the only known mechanism for sustained and significant weight loss."

Kurt D. Newman, the surgeon-in-chief at Children's National Medical Center in Washington, says that until recently he regarded weight-loss surgery as "kind of wrong -- more so in a kid." Prodded by his hospital's obesity specialists and faced with a growing number of 13 year olds weighing 300 pounds and a population that has one of the highest rates of pediatric obesity in the country, Newman has reconsidered. He is recruiting a bariatric surgeon for Children's new Obesity Institute.

David Ludwig, a pediatric endocrinologist at Boston's Children's Hospital and one of the nation's most prominent obesity experts, has also tempered his opposition. For carefully selected patients who have been treated consistently with other methods and failed, Ludwig said, surgery with appropriate safeguards may be an option. But, he warns, these operations are neither a solution to an urgent public-health problem nor a panacea. Bariatric surgery, he said, "can result in horrendous complications, require repeat surgeries and create a whole new set of medical problems.

Thomas Inge, the chairman of the NIH teen bypass study, directs the nation's oldest weight-loss surgery program, at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center. Since 2001, 110 adolescents have undergone surgery there, under guidelines issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

They must have a body mass index, or BMI, of at least 40 (the equivalent of someone who is 5 feet 4 and weighs 235 pounds) and a serious weight-related health problem such as Type 2 diabetes or high blood pressure. Referral by a pediatrician is required. Patients younger than 18 must have failed organized weight-loss attempts and have achieved most of their growth. All must demonstrate preoperative weight loss on a liquid diet and pass psychological screening tests.

The majority of Inge's patients are girls. One year after surgery, they had lost on average one-third of their excess weight, about 30 pounds for someone 100 pounds overweight, for example. Many remained obese but were no longer morbidly so.

Unlike gastric bypass, which is generally covered by insurance and costs about $25,000, lap-band surgery in teenagers is considered experimental, which means that parents typically must finance it.

To pay for Andrew Burrill's 45-minute procedure, his parents sold a vacation time-share.

Andrew, who has lost 52 pounds since the surgery and now weighs 184, said that the required changes in his diet have not been as difficult as he initially imagined. He said he does not miss the daily two-liter bottle of Mountain Dew he used to chug. And he has learned the hard way that if he eats too much -- more than about a half-cup of food at a time -- he vomits.

Adjusting to his dramatic weight loss has been somewhat tougher. Andrew, whose waist size has dropped from 44 to 34, said he still thinks that he looks enormous when he looks in the mirror.

The best thing has been the reactions of other people. "I haven't had one person stare at me since I got the surgery," he said. "And in PE, it's the first time in my life I don't come in last."

Labels: Lap-Band surgery, teen gastric bypass